When it comes to sustainability, the first thing that springs to mind for the textile and fashion industry, as in almost all sectors, is the environmental footprint. Because it is easier to observe and report the concrete effects of issues such as water and energy use or waste management. But what about the social footprint? Do the information and data on social contribution, philanthropic activities or the number of jobs that companies share in their sustainability reports really fall within the scope of social sustainability? Apparently, the situation is not as it is thought.

We talked to Associate Professor Dr. Hakan Karaosman from Cardiff University about what exactly social sustainability means and why it is still not properly understood. Karaosman, who has been conducting research on the sustainability of the fashion and textile supply chain for many years and has achieved significant success in the international arena, is not only a scientist but also the child of a mother who is a textile worker; therefore, he shares his evaluations and solution suggestions regarding the future of the sector with us by combining his observations and experiences from the field as well.

First of all, he underlines that the fashion industry is a human-oriented sector and summarizes strikingly the current state of the sector with the words; “The fashion industry of 300 million humans has forgotten to be human.” When we remind him of his statement “The textile and fashion industry have emotional consequences” which he expressed at an event, and ask what exactly he means here, Karaosman gives the following explanation: “We are in a process in which people are very emotionally distant from each other around the world. However, the textile and fashion industry have emotional consequences. We only talk about a management system focused on product, performance and efficiency. But we do not talk about the condition of a human who is not a machine but does the same job for 10 hours. Brands are emotionally disconnected from their suppliers. The chief can get angry and shout at the laborer in case the work is not finished in time, because the chief is afraid that the person in charge will get angry with him, and this fear chain continues all the way to the top. We need to review these ties.”

“We have still not understood the concept of sustainability”

Karaosman points out that sustainability is generally seen as a risk management model by companies today and is mainly used as a tool for operational efficiency, and emphasizes that the issue must first be understood correctly: “It has been 38 years since the official definition of sustainability was made in 1987, but we keep talking about the same problems today. We still do not understand what sustainability means and how the Triple Bottom Line model consisting of Economic – Social – Environmental pillars should be used. Without understanding these, it is not possible to bring together economic, social and environmental aspects. In addition, there are already conflict points between these three clusters that make a holistic approach difficult. We need to talk about these. In short, if we focus on the side effects of the disease rather than the main cause, we cannot solve the problem, but we can only see temporary improvements.”

What is and what is not sustainability?

In 1987, the United Nations Brundtland Commission defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

For the business world, sustainability does not mean that a company mainly ensures financial continuity by increasing its profitability and reducing its costs, accompanied by social and environmental improvements; it refers to the continuity of a company’s operation in both economic (not only financial), social and environmental dimensions.

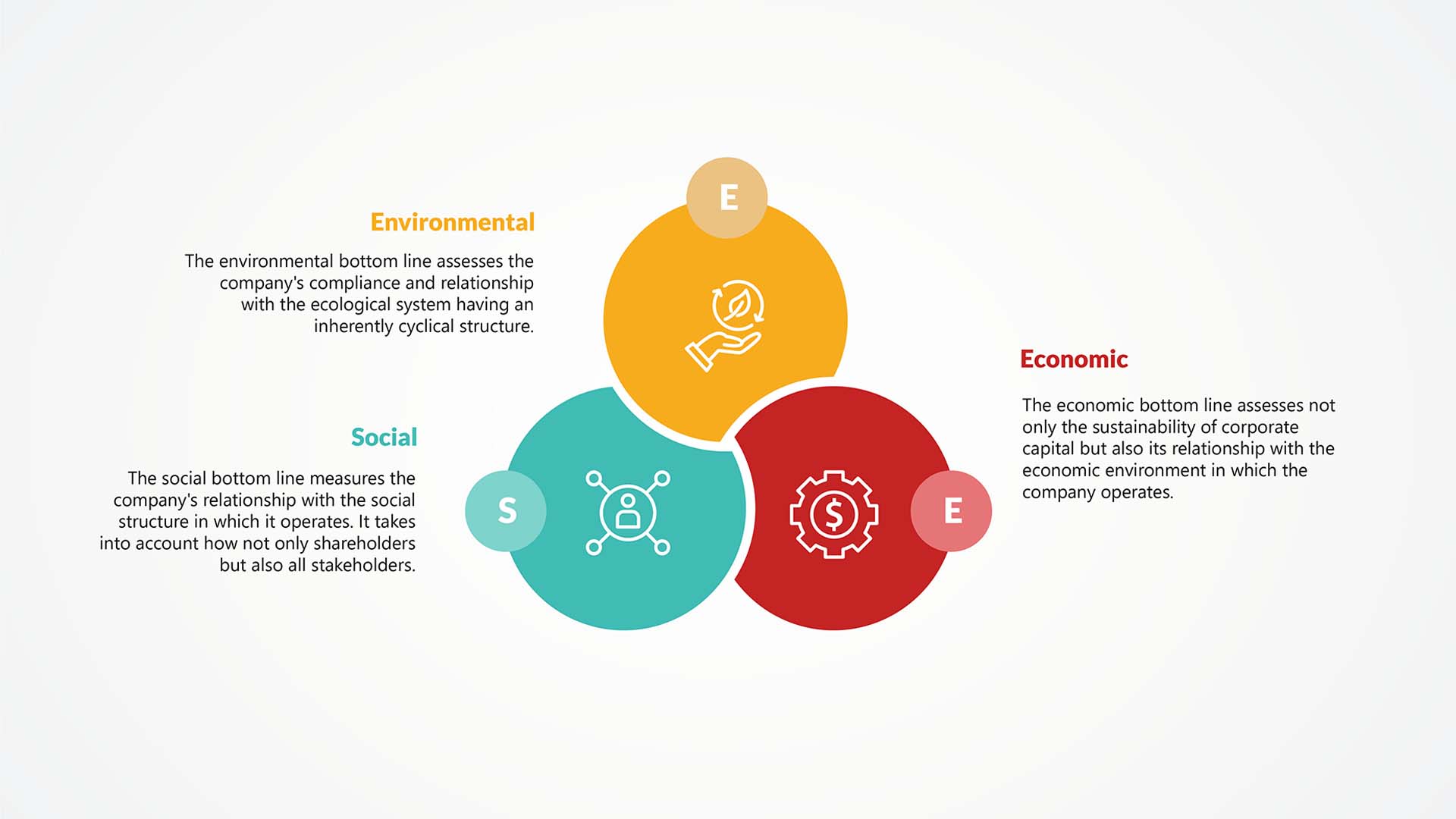

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) model, introduced by John Elkington in 1994, offers a sustainability framework that analyses these three-dimensional impacts of companies. The main idea of the model is to revise the current economic system and move from a profit-oriented approach to a holistic approach with three pillars:

The economic bottom line assesses not only the sustainability of corporate capital but also its relationship with the economic environment in which the company operates. For example, fair labor wages and the impact of the company’s activities on the sustainability of the business of its suppliers.

The social bottom line measures the company’s relationship with the social structure in which it operates. It takes into account how not only shareholders but also all stakeholders, including employees, their families, suppliers and customers, are affected by the company’s activities. This includes, for example, the company’s constant respect for human rights, gender equality, and the provision of a safe and clean working environment.

The environmental bottom line assesses the company’s compliance and relationship with the ecological system having an inherently cyclical structure. Accordingly, for example, the company is expected to comply with this environmental order in its investment decisions and raw material choices.

Although sustainability is divided into 3 clusters, they are actually interconnected. Environmental damage not only disrupts the ecological balance, but also has a negative social impact, for example by compromising access to clean water and food, which is a basic human right, and an economic impact, for example by making the soil infertile and disrupting economic production.

“Progress on social targets is difficult to measure, it is a long-term process”

Associate Professor Dr. Hakan Karaosman states that environmental and economic targets are easier to measure because they are more quantitative; “First of all, we need to underline that. When we look at social sustainability, we are talking about very long-term and difficult-to-measure issues. When brands announce their social targets, we cannot go back later and understand the progress here. That is why social issues are coming slightly behind. We should take our steps patiently, knowing that there will be no feedback in the short term,” he says.

“Social dialogue is the main way to solve problems”

“At the beginning of the speech, I said that there are conflict points between economic, social and environmental clusters that make a holistic approach difficult. The most basic way to solve them is social dialogue mechanisms. For this reason, we need to be with people in the field,” Karaosman emphasizes the importance of interacting directly with those working in the field and states that he spent 7 months in Türkiye and visited suppliers in many provinces and talked to them. He underlines that even the technical terms and words used differ from region to region and therefore dialogues with a standardized language will not achieve their purpose: “What is valid for Italy does not fit Vietnam. We cannot measure all supply chains with 30 standardized questions.”

Explaining that the brands are actually going to the field as a pilot project, Karaosman points out that there are some problems at this point: “There are Management Systems in which fashion brands are involved and these are mostly carried out through third-party auditors. However, researches show that the existing auditing mechanisms cannot make accurate measurements, the data is manipulated and the audits that try to reveal the truth can actually leave the worker in a very difficult situation.”

He also discloses that suppliers, not fashion brands, pay the wages of the auditors and shares the following information about the process: “In Türkiye, manufacturers prefer to work with major international brands by accepting the conditions they offer in order to earn more money. They think, ‘If these are their conditions, I have to follow them.’ However, our supply chain problems cannot be solved because the demands of the brands are so expensive.”

“We made this complex supply chain tangle, and it is in our hands to solve it”

“Things are very busy in the supply chain and no one has time to go to the field in this chaos. In fact, this complexity is exactly the reason why we cannot solve the problems. However, I would like to emphasize that the supply chain is a human-made. We made this complex supply chain tangle, and it is in our hands to solve it,” says Karaosman stating that he is hopeful about the future and continues his words as follows: “Suppliers know the answer to the question of what and how the right practices, the right solution proposals should change. Therefore, it is very important to talk to suppliers and include them in events. And I frankly now attend the events I am invited to if there are suppliers there too.” He adds that in one of his past speeches, he presented the idea of an event where workers’ voices would really be heard, where workers or farmers would be on the stage, and that this was highly appreciated, but no action was taken on the issue afterwards.

We also asked Karaosman about how activism movements aimed at making workers’ working conditions and problems visible contribute to social sustainability. He says that such campaigns have transformative power and that he is personally a supporter too: “Remake, where I am on the board of directors, launched the #payup campaign for workers who were not paid billions of debts during the pandemic, and thus the debts of those workers were paid. So, it is very important to create a collective consciousness here. We all need each other. For this reason, those who really want to say the same thing should support each other without getting into ego wars.”

“We are not consumers, we are stakeholders”

Lastly, we ask Associate Professor Dr. Hakan Karaosman about the role of consumers in sustainability, and he underlines that he does not consider the word ‘consumer’ as correct and that it should be called ‘stakeholder’ instead: “We should move away from these passive missions and divisive language. We are all both consuming and producing stakeholders. As consuming stakeholders, our biggest power is our purchasing power and we should use it wisely.

I would also like to draw attention to Bluewashing, which is the social equivalent of Greenwashing. Together with my dear friend, colleague and supervisor Prof. Donna Marshall, we have coined the term Social Offsetting instead of Bluewashing. Here, we mean that companies that create a negative social impact try to offset it through marketing. For example, a company that produces on demand and has no pre-consumer waste presents itself as quite sustainable but does not mention post-consumer waste. In the operations management literature, there is a phrase called ‘garbage in, garbage out’. If the product you already use becomes rubbish, you are actually buying rubbish. You have no chance to use it in the long term.”

While concluding our speech, he once again reminds the importance of creating social dialogue mechanisms and concludes his words as follows: “As much as we want to position artificial intelligence or technological solutions as if they will create a magical solution, if the only purpose of your business model is to make money and increase your income, the increase in that income equals the negative impact you create in the supply chain. A t-shirt produced for 2 euros cannot provide a living wage for the workers in that supply chain.

When we talk about social justice, there are 3 sub-headings. One of them is relationships. How strong is the communication between us and how positive is my evaluation of the way the other person talks to me? Because if it is negative, this is injustice. The second is decision-making processes. How inclusive is this? How much do you include me when you are making a decision about something? The third is risk and benefit distribution. How much do I share the risks and benefits? Modern industrialization fails in all of these. Because the reason for the survival of modern industrialization is exclusion, which is the opposite of inclusion. So, this is a systemic problem and solving it is a long journey. And to repeat, the only thing that needs to be done for this journey is to create social dialogue mechanisms to ensure harmonization with all stakeholders. There are very good countries that have achieved this harmonization, and most of them are tribal countries in the South. Because these people already know very well how to live with nature, as they have to struggle to survive by it. But when we look at the decision-makers, these are Northern countries. We cannot learn from the Northern countries how to live like the Southern countries. This is exactly the problem and the solution also lies here.”